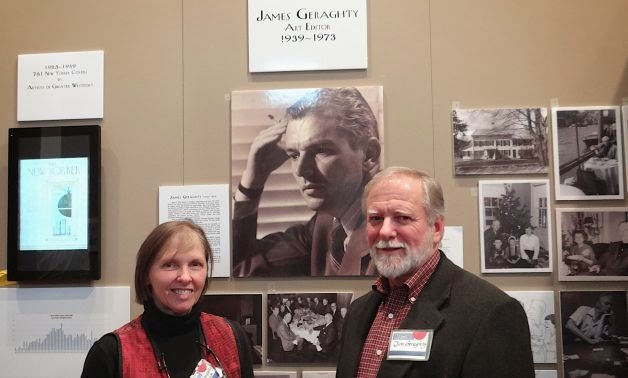

If you live in New York City, you know Sam Ferri's work. Sam comments on urban life in his "Misconnected" single panel cartoon, which was in a couple of NYC papers. Or maybe you saw it in Funny Times. Here's one of my favorites that we talk about in the interview below:

But Sam gathers no moss. He's a multi-tasker; a cartoonist, painter and animator, equally comfortable with old school and new techniques. His clients include

Time Out New York (where he drew the

"Photo Finish" feature)

, The New York Post, The Jerusalem Post, The NYPress, The Brooklyn Paper, The Brooklyn, Rail, Funny Times, A and E Biography, Jack Daniels and others.

He has a

new animated short. It's for Jack Daniels and it's part of a series by different animators. Each animator was given the audio of a real life Brooklyn bartender and then they (the animator) created a short based on it. Viewers vote for which animation they like best. Please consider voting.

This interview was conducted via email earlier this month. I'm grateful to Sam for taking the time out of his busy schedule to give thoughtful and thorough answers about the challenge of being a cartoonist during this time in history.

INTERVIEW: SAM FERRI

Mike Lynch: Are you from a big family? Does anyone else in your family have artistic tendencies?

Sam Ferri: I did some research and found that the average family size is 3.14. So, between myself, my parents and 2 younger brothers, I guess that would make us subjectively larger than average.

Both of my parents actually met at R.I.S.D. where my father was studying photography and my mother, sculpture. Both are very talented and continue to produce interesting work to this day. I would say most of my artistic training was gleaned informally from growing up in the house with them. Also, as a skilled web designer, my father has actually helped me in building and maintaining my site. I kind of got lucky with all that stuff.

Mike Lynch: Did you go to art school?

Sam Ferri: I attended your average liberal arts college for 1 year and then opted out. I’ve often gone back and forth wondering if this was a mistake, but for now seem to be doing okay without it, and compared to my brother finishing law school, my debt is minimal. I suppose when he enters his field and starts making money that dwarfs that of my puny cartoon paychecks I might feel differently, but I think the moral here is that it’s okay to drop out of college and become an artist if you properly set up in advance having a sibling you’ll be able to mooch off of.

Mike Lynch: Do you have favorite creators (living or dead) who inspire you? Can you name a few off the top of your head?

Sam Ferri: In no particular order:

Red Grooms, Bob Dylan, Woody Allen, Norman Rockwell, Winsor McCay, Jules Feiffer, Bill Watterson, Gary Larson, Shel Silverstein, Weegee, Mark Twain, Dr. Seuss, Charles Schulz, most of the artists who ever worked on Mad Magazine (Particularly the first 25 issues and also Sergio Aragonés), John Callahan, Jeffrey Lewis, Chris Ware, Art Spiegelman, Will Eisner, Maurice Sendak, Alison Bechdel, Seth, Honoré Daumier, Jack Kirby, Ray Bradbury, Phillip K Dick, Andy Kaufman, George Carlin, Louis C.K., Rod Serling, The Kinks, The Rolling Stones, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, Charlie Kaufman, Charles Bradley, Charlie Chaplin, Charlie Parker, Adrian Tomine, Lenny Bruce, George Herriman, Peter Arno, A.B. Frost, R. Crumb, Yoshihiro Tatsumi, Neil Gaiman, John Steinbeck, Robert Sikoryak, Jerry Moriarty, Roald Dahl, James Thurber, Ralph Ellison, Miyazaki … (This list could continue. The more I think about it, the more brilliant people come to mind, but this is getting absurdly long. Despite the fact that I’ll kick myself later for leaving a number of people out, let's end it here.)

Mike Lynch: Your writing hinges on observational humor and irony. Do you have to go hunting for ideas? Are the ideas in Misconnected for real or are they written? I mean, like, "The Eternal Optimist" -- is it something you saw and then came up with the tag line or are they fiction? A mix of the two?

Sam Ferri: It’s probably a healthy mix of the two. Every idea is inspired by something I saw or experienced, but I think, just like any individual, the world is filtered through one's own warped perceptions of it. I probably have a tendency to be looking for this sort of stuff.

There’s a really neat experiment where a viewer is shown a video of people playing basketball and asked to count the number of times the players make a pass. Meanwhile, at some point in the video, a random person in a gorilla suit walks across the screen, and more than half the time, when asked later, the viewer will not remember having seen the gorilla because they are so focused on the task of counting. I think, metaphorically speaking, that like some other people out there, I work in reverse; I lose track of how many times the ball is passed because I’m so busy trying to spot gorillas. I don’t feel like I have to hunt cartoon ideas out most of the time. There are gorillas everywhere. Mostly, I think it’s just about being open to seeing them.

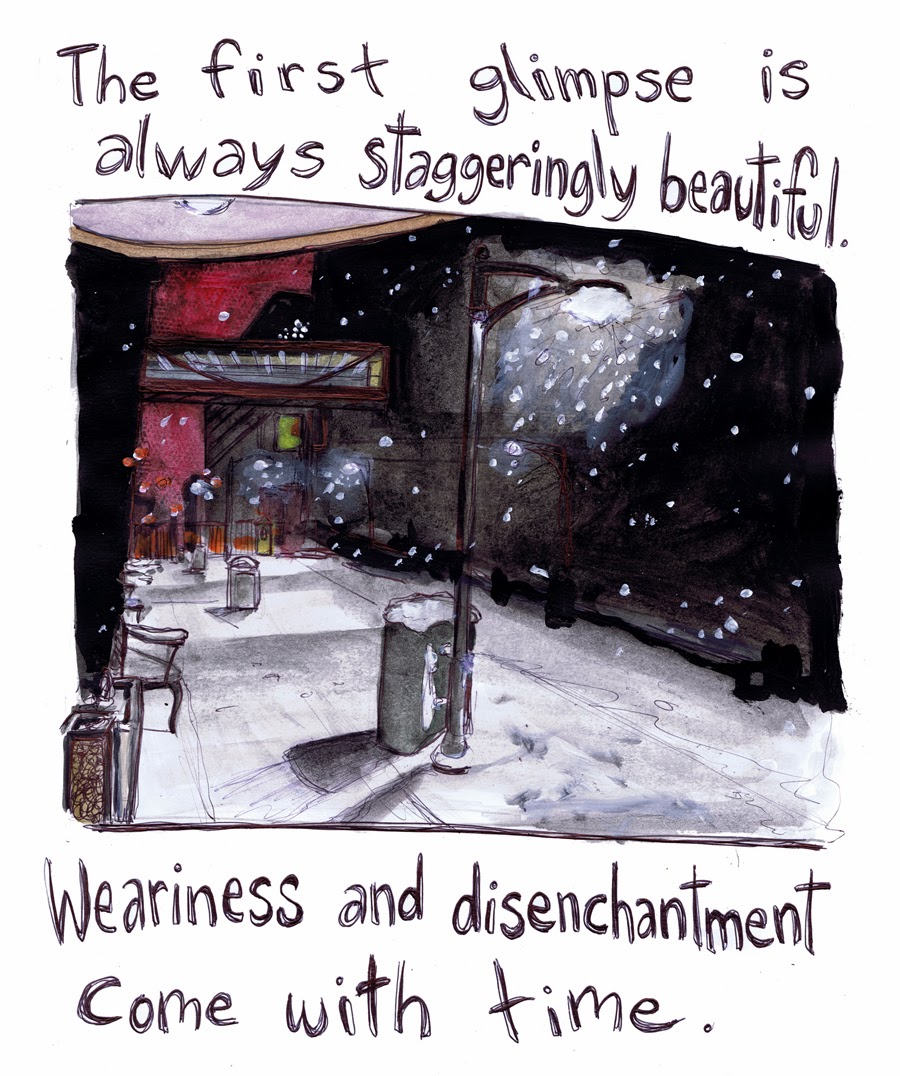

Mike Lynch: In "Got Hemorrhoids" it's like we are sitting next to a driver and he's in the middle of a story -- which the road sign outside has reminded him of (maybe). The photographic fisheye POV makes it documentary-like, and more like a brief visual New Yorker "Casual," than a gag-driven single panel cartoon. Would you agree?

Yes, I think so. This is part of a series that I’ve named ‘Misconnected'. A couple of years into it, I discovered the travel cartoons that Shel Silverstein had created for Playboy (

http://www.amazon.com/Playboys-Silverstein-Around-World-Shel/dp/0743290240/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1300207344&sr=8-1). In these, we follow the artist as he travels across the world, each piece drawn from the eyes of someone with a sense of innocence, making all of the clever pratfalls of any average traveller. Unusual to most gag comics, Shel has drawn himself into all of them. However, he simply functions as a stand-in for the reader. This is not terribly different from any gag cartoon which is essentially a composite of relatable symbols and stand-ins for universal experiences that we laugh at because we see ourselves in them.

What I was thinking about in my own Misconnected series was to take out the middle-man and attempt something slightly more literal; to have everything appear as if out of the eyes of the reader, have the characters within the comic look as if they are addressing the reader directly instead of another character on the page, or create a scene as vividly as possible to make the reader feel like a truly present observer in that moment.

I think I’ve had mixed results selling these in some venues because they do buck the usual cartoon formula a little bit. I'm particularly fond of those artists like Winsor McCay or Bill Watterson who were constantly playing with and challenging the visual formula in their work, rather than relying on the safety of them, often blurring the invented line between comics and fine art.

Mike Lynch: If you go to your "About" page at your Misconnected site, we see a "Wet Paint" sign, shoes on a city street, an Italian ice and other urban images. These are drawn/painted with different old school (non digital) techniques and it seems that almost each element is drawn in a different way. Which materials did you use? When doing your Misconnected series, what is your medium of choice? Why the choice of old school techniques over digital?

Sam Ferri: I love to paint and do work by hand. When I started out, I refused to touch computers, thinking that I was holding onto some of the techniques I admired that seemed to be on the wane. These days, I switch back and forth depending on the project. I feel like I’ve come to see different techniques as tools in the toolbox, each appropriate in its own time. There are some things that are only achievable using computers and the same can be said vice versa.

I use a lot of pen and not very much pencil. I like creating lines spontaneously that I have to commit to. Sometimes I like attempting to do a final draft in pen without outlines or a light box, creating mistakes along the way like playing Houdini, chaining yourself in a tight spot and then attempting to get out of it. I used to use a lot of ballpoints, but grew out of that and am currently obsessed with a .1mm Uniball by the name of Impact 207. These are kind of expensive for my taste, but they have the thickest, juiciest lines. I’ll do fills in water colors, acrylics or Photoshop.

Mike Lynch: The "Thoughts of an Artist In Time of Recession" piece is very true to me. Looking for new markets, promoting your work -- it's an uphill fight. You've had clients come and go. Do you want to talk about that? And what happens when a major client decides to stop buying your work? Does a new one step in? Where do you see yourself in five years?

Sam Ferri: That’s a tougher question. Let’s go back to the size of my family.

Hmmm… Well...Honestly, I don’t know. I grew up on the cusp of a lot of changes in the world of comics. I hear a lot of voices of doom from more experienced cartoonists, some I’ve met on visits to try my stuff at

The New Yorker and then others like Scott McCloud or Art Speigelman seem to have a lot to say about incredible untapped potential in the field. Certainly, both the audience and the number of people interested in creating comics and cartoons has grown dynamically. The problem is the number of markets that have dried up or grown stale. Many seem to have had a hard time adapting to new media forms. I worked on weekly comics for both the NYPress and Time Out New York before they decided to cut their comics sections to cut costs. And while I don’t think certain magazines and newspapers have been agile enough to transition or realize potential reader interest, new online markets and venues have formed that are filling that demand. The trouble is that there’s such a saturation of material online that these venues are slow to adapt to a model that pays decently for contributions. How does one then make a living at a job where only those in the top tier make a decent living wage?

I think the answer is similar to advice you gave a reader on this blog not long ago. Branch out. Do not personalize failure or rejection because there’s a lot of it coming and despite whatever plateau of success you may think you’ve achieved there’s probably a lot more to come. Often times I feel like Ralph Kramden from the Honeymooners, each week coming up with a new scheme for a niche I could fill or a million dollar concept that will solve everything, only to get slapped back down by status quo. On the other hand, the rapid growth of technology has created a wide open frontier for the intrepid artist to evolve into something new. Maybe in the words of Horace Greeley, it’s time to “Go West!” and maybe one of these schemes will bear fruit.

I’ve been doing a lot of animation lately. That seems promising. I’ve been thinking about doing a new series of my aforementioned comic-strip as 15-20 second shorts. I’m also planning on putting out a book collection of my comics relatively soon either through a publisher or independently if necessary. This all game is simultaneously incredibly rewarding but also a constant struggle, so in five years… who knows? I am open to suggestions.

Mike Lynch: You have a couple of clients (A and E Biography, Jack Daniels) that you have been doing animation for. Can you tell me about the Jack Daniels project? How did it come about?

Sam Ferri: Essentially, Jack Daniels found 8 bartenders to tell a story about one of their bar tending experiences. Each of those recordings were then handed off to different animators commissioned to do with them as they would. Up until the 30th, people can vote on the story they like most and the winning bartender goes on a trip to Tennessee. I’m not biased or anything, but I think you should vote for mine.

In all seriousness, they are all interesting and worth checking out.

The other project you mentioned for A and E is a short piece about the artist Seurat and his painting Sunday on La Grande Jatte. Though it’s completed, I can’t tell you when it'll be released. Soon, I think.